A team of scientists working on a boat off Cape Cod have just landed a huge great white shark, named it Genie, tagged it and returned it to the sea. They hope to track it and learn about the enigmatic lives of these ancient predators. Meanwhile, on Mars, Nasa's Curiosity rover has begun its mission to determine – metre by metre, rock by rock – whether the red planet was once able to support life. This new mission comes days after Curiosity captured a partial solar eclipse on Mars as its small moon Phobos crossed the face of the sun, appearing to take a tiny bite out of it.

And in the art world … well, let's see.

It has been announced that Damien Hirst got record attendances for his Tate Modern retrospective, while drawings by Andy Warhol are among works to be exhibited at the inaugural Frieze Masters art fair next month. Somehow, these bits of art news do not seem as thrilling as discovering the secrets of other planets, or the once-unfathomable oceans.

Many projects today try to bring together art and science. London's Wellcome Collection does a resourceful job of marrying medical science and art in its exhibitions, for example. And Cern, home of the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, has an arts programme that verges on the avant-garde, with dancers impersonating particles in the site's library, among physicists deep in study. The two areas are generally held to have a lot to teach one another. But there is another way of looking at their relationship. Is it possible that, in the modern world, science has simply replaced art? By that I mean, replaced its higher purpose of expanding minds and imaginations and revealing the beauty of existence.

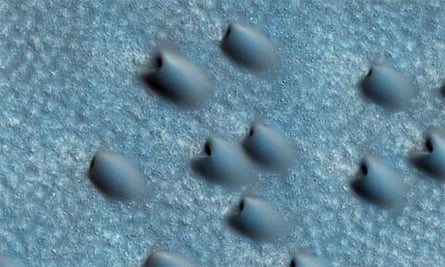

It is science that now provides the most beautiful and provocative images of our world – not to mention other worlds. It is hard to name an image made by an artist in the last two decades that is as fascinating or memorable as, say, the Hubble telescope's pictures of the Eagle Nebula or the Whirlpool Galaxy. A visit to the Hubble's website (hubblesite.org), with its tours of the cosmos, its astronomy photographs (free to print) and its movie theatre chronicling the birth-throes and death-pangs of stars, is arguably as rewarding as a trip to any museum. And then there are all those images of deep-sea worlds taken by submersibles, among them National Geographic's shots of the deepest hydrothermal vents ever discovered. Emissions from these volcanic chimneys, nicknamed "black smokers" and located three miles below the surface of the Caribbean Sea, provide extraordinary images; they are also hot enough to melt lead.

Yet it is not on purely visual grounds that science seems to dwarf today's art. Proponents of contemporary art are quick to point out that it is not necessarily about the visual. Ever since the rise of conceptual art in the late 1960s, art has claimed an intellectual territory of provocation and contemplation beyond the visible. Yet it is here that science wins hands down. What notion of any current artist can compare with the sublime craziness of quantum physics (in which objects can exist in multiple states and places at the same time), let alone the awe-inspiring prediction and apparent discovery of the Higgs boson after a 45-year search? Here is the real conceptual art, and it turns your head inside out merely trying to grasp its most basic premises – in particular, that all the matter we can see appears to comprise just 4% of the universe, the Higgs providing a possible gateway to understanding that remaining 96%.

Once, art and science truly worked as equals – in the researches of Leonardo da Vinci, for instance. In the 21st century, art rarely rivals the capacity for wonder that modern science displays in such dazzling abundance.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion